Image: Intel

Image: IntelIt sounds crazy, but it’s true: Arch-rivals AMD and Intel have teamed up to co-design an Intel Core microprocessor with a custom AMD Radeon graphics core inside the processor package, aimed at bringing top-tier gaming to thin-and-light notebook PCs.

Executives from both AMD and Intel told PCWorld that the combined AMD-Intel chip will be an “evolution” of Intel’s 8th-generation, H-series Core chips, with the ability to power-manage the entire module to preserve battery life. It’s scheduled to ship as early as the first quarter of 2018.

Though both companies helped engineer the new chip, this is Intel’s project—Intel first approached AMD, both companies confirmed. AMD, for its part, is treating the Radeon core as a single, semi-custom design, in the same vein as the chips it supplies to consoles like the Microsoft Xbox One X and Sony Playstation 4. Some specifics, though, remain undisclosed: Intel refers to it as a single product, though it seems possible that it could eventually be offered at a range of clock speeds.

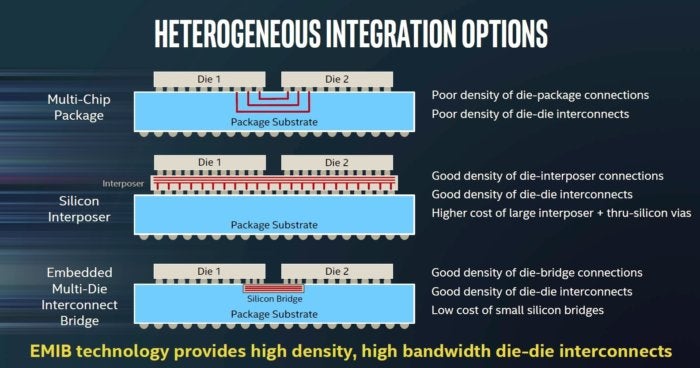

The linchpin of the Intel-AMD agreement is a tiny piece of silicon that Intel began talking up over the past year: the Embedded Multi-die Interconnect Bridge, or EMIB. Numerous EMIBs can connect silicon dies, routing the electrical traces through the substrate itself. The result is what Intel calls a System-in-Package module. In this case, EMIBs allowed Intel to construct the three-die module, which will tie together Intel’s Core chip, the Radeon core, and next-generation high-bandwidth memory, or HBM2.

Editor’s Note: Some people are beginning to refer to this chip as the Kaby Lake G, a name that Intel representatives said they will not confirm. A spokeswoman referred to it as “rumor and speculation.”

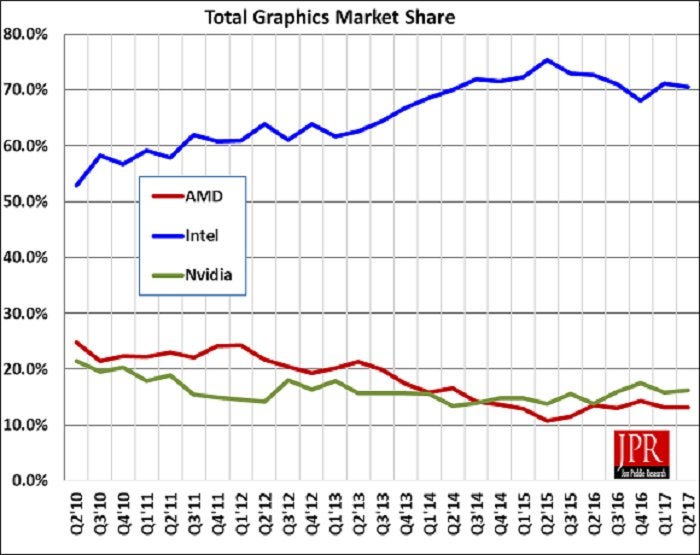

The story behind the story: You heard right: This is AMD and Intel, working together. Shaking hands on this partnership represents a rare moment of harmony in an often bitter rivalry that began when AMD reverse-engineered the Intel 8080 microchip in 1975. But in graphics, the two are much more cordial: Intel’s low-end, integrated cores own the majority of the notebook PC market, while AMD is pinched between Intel and Nvidia’s high-end chips. Intel, meanwhile, is no friend to Nvidia, having paid out $1.5 billion in licensing fees since 2011. The enemy of my enemy is my friend—that’s one explanation for how the deal came about.

Mark Hachman / IDG

Mark Hachman / IDGIntel showed a reference notebook of the sort that will be enhanced by the AMD-Intel partnership. The large, black blank space is designed to be used for drawing with the stylus and for other digital content creation.

AMD and Intel: A win-win for all concerned

According to Chris Walker, vice president of Intel’s Client Computing Group, Intel had a problem: AAA gaming PCs were selling, customers were interested in VR, but notebooks with the graphics horsepower to run them were thick and heavy. Customers, though, were seeing growth in two-in-one PCs and even thinner thin-and-light PCs. This was what Walker called Intel’s “portability obstacle:” How could it bring top-tier performance to notebooks that didn’t weigh a ton?

The answer, as it turned out, was the EMIB, a small sliver of silicon to bridge discrete logic cores within a single chip package. Intel had originally developed the EMIB as an alternative to what’s known as a silicon interposer, the “floor” or “foundation” of a multichip module. The problem with an interposer is that, like a floor, it needs to cover the entire space underneath the module, making it expensive to manufacture. EMIBs are more like small connectors that dip into the substrate. Intel found that they worked for its Altera programmable logic line as well as its more mainstream PC microprocessor designs. In fact, this is the first consumer use of EMIB, executives said.

Intel

IntelThis slide, taken from an Intel presentation, shows how Intel believes its Embedded Multi-die Interconnect Bridge is more cost-effective for connecting chips than methods that use an interposer, and far higher in performance than Multi-Chip Package designs.

Intel’s EMIBs, though, allowed another important advantage: modularity. Originally, Intel positioned EMIBs as a tool to mix and match chips using different process technologies. When designing a programmable chip, adding in third-party logic cores is somewhat common. Within integrated logic as complex as a microprocessor’s, though, it’s nearly unheard of. The EMIB allowed for a compromise, placing CPU, GPU, and memory in close proximity without being part of the same actual design.

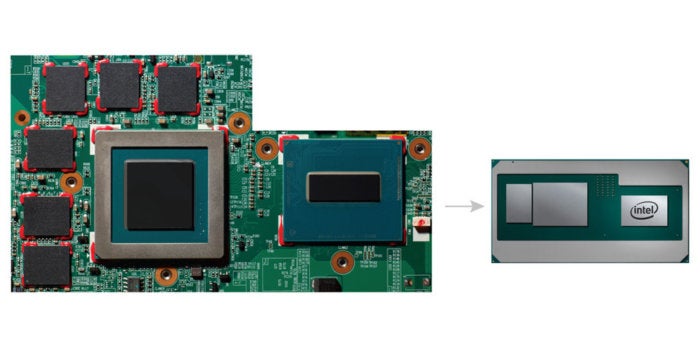

That paid off almost immediately. Intel’s still being cagey on all the benefits of the Core-Radeon module that EMiB enabled, but the company revealed two. According to Walker, the module stripped out a whopping 1900 square millimeters (2.9 sq in.) from a more traditional motherboard, where the processor, discrete GPU, and memory were laid out next to one another. (Put another way, the EMIB layout consumes just half of the typical board space, Intel says.) Second, the module uses about half the memory power of a traditional design.

Intel

IntelAn example of the space savings Intel achieved by moving the CPU, Radeon GPU, and HBM inside the processor package.

Software, drivers are critical for managing power

That’s important, because heat naturally becomes more of an issue as notebooks become thinner. Intel added what it calls a new power-sharing framework to the module, consisting of a new connection between the processor, GPU, and memory. Just as a system can manage the processing workload between the three components, the new power framework can do the same for power management.

Here, Intel’s software team plays a critical role, both in managing power as well as ensuring that the right drivers are in place for optimizing performance.

“If I look at this as one system with one driver package, with one Intel-delivered driver set, we’re able to apply things like our Dynamic Platform Framework,” Walker said, referring to a set of Intel-designed thermal management technologies that can manage the CPU, GPU, and memory simultaneously.

The Dynamic Platform Framework will allow the system to tweak and balance the three platform components dynamically, based on workload, system state, the temperature of the PC chassis, and more. Naturally, tasks like movie playback will still be routed to the Core chip’s existing, integrated graphics core, Walker said. The integrated 8th-gen Core chips already contain dedicated, optimized logic to play back 4K video using the HEVC or VP9 codecs chosen by streaming content companies like Netflix and Amazon, while using minimal power.

One interesting wrinkle: Intel will be responsible for supplying the drivers for the Radeon GPU, though company engineers won’t write the original code. An Intel representative said they’re working closely with AMD’s Radeon business to supply “day one” drivers for new games, when those drivers become available.

Here’s a video Intel authored, explaining how it all works:

Intel’s graphics business is alive and well

Speculation that Intel might license or outright buy AMD’s Radeon business has circulated for years, especially as AMD has struggled to achieve profitability. AMD, however, enjoyed a rare profit of $71 million on $1.64 billion revenue for the just-completed third quarter, helped by sales of its Ryzen processors and Vega graphics chips. AMD’s semi-custom business, which usually sells chips to game consoles, could use a boost: It reported flat sales year-over-year. (AMD also said it closed an unspecified patent licensing transaction “which positively impacted revenue,” though officials confirmed that the Intel deal wasn’t it.)

Jon Peddie Research

Jon Peddie Research Intel has dominated the PC graphics market, thanks to the integrated graphics cores inside its Core processors.

It’s possible that the Core-Radeon (Core-R, perhaps?) deal may yield a longer-term relationship. But right now, AMD seems to be positioning it as a single contract with a customer, like any other.

“We’re constantly looking at different things inside AMD, but this is really Intel’s project,” said Scott Herkelman, the corporate vice president and general manager within the Radeon Gaming business unit within AMD. “It’s completely semicustom…I wouldn’t say that we’re going to take this and learn something from it. This is Intel’s project, and we’re helping them execute on it.”

Last January, speculation rose that Intel and AMD had signed a Radeon licensing deal, prompting talk that Intel might be preparing to lay off or otherwise get rid of its own integrated graphics development teams. Walker denied it. “Not at all,” he said.

“As we drive mainstream thin and light to 15mm and lower, the Intel UHD solution is still the market leader in terms of how graphics gets delivered on a PC platform,” Walker added. Nor has Intel licensed the EMIB technology to AMD, he said.

AMD representatives went further, stating that there is no patent or IP licensing in place between the two firms at all.

What’s next? Answering the questions

Unfortunately, we still don’t know the answers to several basic questions: How fast will these new cores run? How many variants of these new Core-Radeon chips will there be? What Intel Core architecture—Kaby Lake, or Kaby Lake-R—are they based upon? Does HBM2 memory confirm that the Radeon core is based upon the AMD “Vega” architecture, and how does it compare to existing chips? How much memory is inside the package? Will the new Core-Radeon modules incorporate AMD-specific features such as VSR, Eyefinity, and Async Compute? And, of course, how much will it all cost?

The latter two questions can be answered in broad strokes. The idea, according to an AMD representative, is that these notebooks won’t be priced in the value segment at all, but in the neighborhood of $1,200 to $1,400 apiece. Meanwhile, Intel executives say that notebook PCs based on the new H-series, Core-Radeon modules will move gaming-class graphics down from systems 26mm thick, to thin-and-light PCs at 16mm and even 11mm thick — that’s slimmer than the original 13-inch Apple MacBook Air, and priced accordingly. (To get a sense of just how thin this is, see our 2012 review of the Acer Aspire S5. A laptop based on the Core-Radeon module would be far, far more powerful, however.)

An AMD representative also said that there’s nothing prohibiting any AMD graphics technology like VSR from being included in the Core-Radeon chip—but that in terms of specifics, it’s up to Intel to decide.

According to Intel representatives, we’ll get more of those answers closer to launch. For now, however, there’s the simple surprise that the two sides came together to make this happen. For those who have watched the acrimonious AMD-Intel relationship play out in court, in the market, and behind closed doors for several decades, even a limited contract seemed out of the realm of possibility. But now, who knows what the future holds?

Updated at 12:20 PM to add a reference to Kaby Lake G.