Image Credits: Bryce Durbin / TechCrunch

Image Credits: Bryce Durbin / TechCrunch

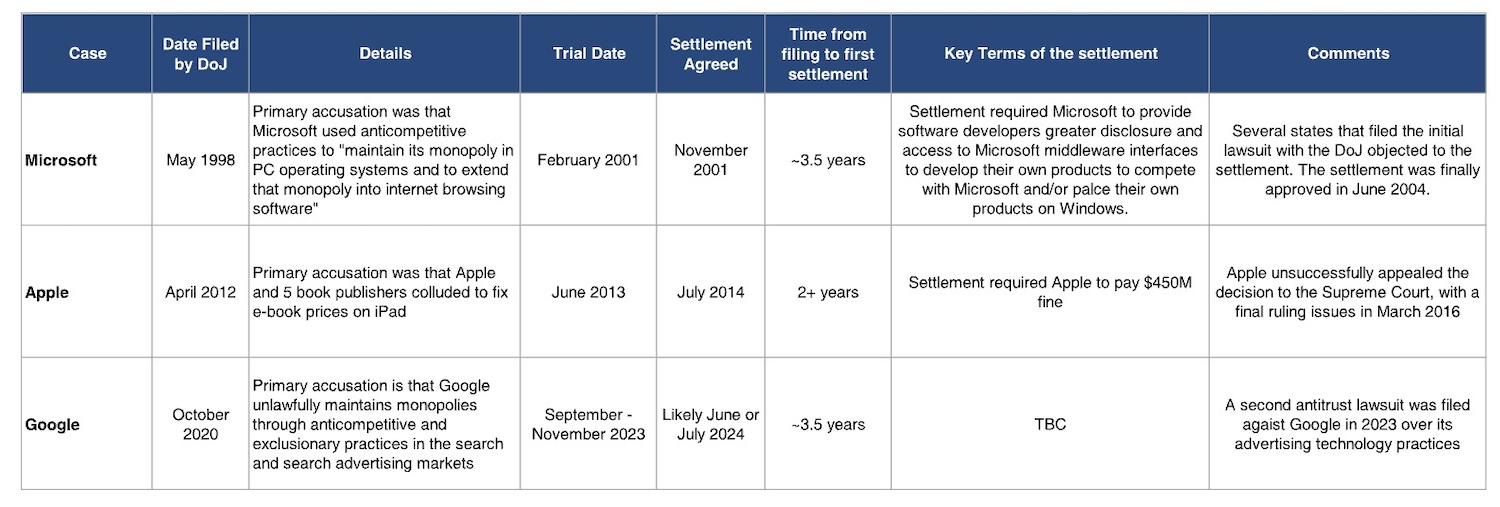

On home turf, Apple has enjoyed many years of relatively light regulatory scrutiny compared to Big Tech peers. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) opened a monopoly case against Google back in October 2020, for instance. It followed with a second antitrust case at the start of last year, targeting Google’s adtech. While the FTC has been pursuing an antitrust case against Meta over a similar timeframe. And who could forget Microsoft’s Windows era tango with U.S. antitrust enforcers?

Thursday’s DOJ antitrust suit, accusing Apple of being a monopolist in the high-end and U.S. smartphone markets, where the iPhone maker is charged with anti-competitive exclusion in relation to a slew of restrictions it applies to iOS developers and users, shows the company’s honeymoon period with local law enforcers is well and truly over.

But it’s important to note Apple has already faced competition scrutiny and interventions in a number of other markets. More international trouble also looks to be brewing for the smartphone giant in the coming weeks and months ahead, especially as the European Union revs the engines of recently rebooted competition rules.

Read on for our analysis of what’s shaping up to be a tough year for Apple, with a range of antitrust activity bearing down on its mobile business.…

Antitrust trouble in paradise

Earlier this month, European Union enforcers hit Apple with a fine of close to $2 billion in a case linked to long-running complaints made by music streaming platform Spotify, dating back to at least 2019.

The decision followed several years of investigation — and some revisions to the EU’s theory of harm. Most notably, last year the bloc dropped an earlier concern related to Apple mandating use of its in-app payment tech, to concentrate on so-called anti-steering rules.

Under its revised complaint, the Commission found Apple had breached the bloc’s competition laws for music streaming services on its mobile platform, iOS, by applying anti-steering provisions to these apps, meaning they were unable to inform their users of cheaper offers elsewhere.

The EU framed Apple’s actions in this case as harmful to consumers — who they contend lost out on potentially cheaper and/or more innovative music services, as a result of restrictions the iPhone maker imposed on the App Store. So the case ended up not being about classically exclusionist business conduct — but “unfair trading conditions” — as the bloc applied a broader theory of consumer harm and essentially sanctioned Apple for exploiting iOS users.

Announcing the decision earlier this month, EVP and competition chief Margrethe Vestager summed up its conclusions: “Apple’s rules ended up in harming consumers. Critical information was withheld so that consumers could not effectively use or make informed choices. Some consumers may have paid more because they were unaware that they could pay less if they subscribed outside of the app. And other consumers may not have managed at all to subscribe to their preferred music streaming provider because they simply couldn’t find it.

“The Commission found that Apple’s rules result in withholding key information on prices and features of services from consumers. As such, they are neither necessary nor proportionate for the provision of the App Store on Apple’s mobile devices. We therefore consider them to be unfair trading conditions as they were unilaterally imposed by a dominant company capable of harming consumers’ interest.”

The penalty the EU imposed on Apple is notable, as the lion’s share of the fine was not based on direct sales — music streaming on iOS is a pretty tiny market, relatively speaking. Rather, enforcers added what Vestager referred to as a “lump sum” (a full €1.8 million!) explicitly to have a deterrent effect. The level of the basic fine (i.e., calculated on revenues) was just €40 million. But she argued a penalty of few millions of euros would have amounted to a “parking ticket” for a company as wealthy as Apple. So the EU found a way to impose a more substantial sanction.

The bloc’s rules for calculating antitrust fines allow for adjustments to the basic amount, based on factors like the gravity and length of the infringement, or aggravating circumstances. EU enforcers also have leeway to impose symbolic fines in some cases.

Exactly which of these rules the Commission relied upon to ratchet up the penalty on Apple isn’t clear. But what is clear is the EU is sending an unequivocal message to the iPhone maker — a deliberate shot across the bow — that the era of relatively light touch antitrust enforcement is over.

This same message is essentially what the DOJ came to tell the world this week.

During a March 4 press conference on the EU Apple decision, Vestager conceded such a deterrent penalty is rare in this type of competition abuse case — noting it’s more often used in cartel cases. But, asked during a Q&A with journalists whether the sanction for user exploitation marks a policy shift for the bloc’s competition enforcers, she responded by saying: “I think we have an obligation to keep developing how we see our legal basis.”

By way of example, she pointed to discussion about the need for merger reviews to factor in harm to innovation and choice — that is, not just look narrowly at impact on prices. “If you look at our antitrust cases, I think it’s also very important that we see the world as it is,” she added, going on to acknowledge competition enforcers must ensure their actions are lawful, of course, but stressing their duty is also to be “relevant for customers in Europe.”

Vestager’s remarks make it clear the EU’s competition machinery is in the process of shifting modus operandi — moving to a place where it’s not afraid to make broader and more creative assessments of complaints in order to adapt to changed times. The EU Digital Markets Act (DMA) is, in one sense, a big driver here. Although the ex ante competition reform, proposed by the Commission at the end of 2020, was drafted in response to complaints that classic competition enforcements couldn’t move quickly enough to prevent Big Tech abusing its market power. So the underlying impetus is — exactly — the problem of tipped digital markets and what to do about them. Which brings us right back to Apple.

It’s no accident whole sections of the DMA read as if they’re explicitly targeted at the iPhone maker. Because, essentially, large portions of the regulation absolutely are. Spotify and other app developers’ gripes about rent gouging app stores have clearly bent ears in Brussels and found their way into what’s — since just a few weeks — a legally enforceable text across the EU. Hence the requirements on designated mobile gatekeepers to allow things like app sideloading; to not block alternative app stores or browsers; to deal fairly with business users; and let consumers delete default apps, among other highly specific behavioral requirements.

The anti-steering restrictions Apple applied to music streaming apps were prohibited in the EU on March 4, when Vestager issued her enforcement decision on that case. But literally a few days later — by March 8 — Apple was banned from applying anti-steering restrictions to any iOS apps in the EU as the DMA compliance deadline expired.

This is the New World order being imposed on Cupertino in Europe. And it’s far more significant than any one fine (even a penalty of nearly $2 billion).

The bloc has taken other actions against Apple, too. It was already investigating Apple Pay back in 2020 — one obvious area of overlap with the DOJ case, as colleagues noted yesterday.

In January, Apple offered concessions aimed at resolving EU enforcers’ concerns about how it operates NFC payments and mobile wallet tech on iOS. These included proposing letting third party mobile wallet and payment service providers gain the necessary access to iOS tech to be able to offer rival payment services on Apple’s mobiles free of charge (and without being forced to use its own payment and wallet tech). Apple also pledged to provide access to additional features which help make payments on iOS more seamless (such as access to its Face ID authentication method). The company also pledged to play fair in the criteria applied for granting NFC access to third parties.

U.S. competition enforcers have a lot of similar concerns about Apple’s behavior in this area. And it’s notable that their filing makes mention of how Apple is opening up Apple Pay in Europe. (“There is no technical limitation on providing NFC access to developers seeking to offer third-party wallets,” runs para 115 of the DOJ complaint. “For example, Apple allows merchants to use the iPhone’s NFC antenna to accept tap-to-pay payments from consumers. Apple also acknowledges it is technically feasible to enable an iPhone user to set another app (e.g. a bank’s app) as the default payment app, and Apple intends to allow this functionality in Europe.”)

The obvious subtext here is: Why should iOS developers and users in Europe be getting something iOS developers and users in the U.S. are not?

Remember that, as we dive into other regulatory action targeting Apple overseas. Because as the EU enforces its shiny new behavioral rulebook on Apple, forcing the company to unlock and (regionally) open up different aspects of its ecosystem — from allowing non-WebKit-based browsers to letting iOS users sideload apps — U.S. government lawyers may well find other reasons to nitpick the iPhone maker’s more locked down playbook on home turf.

What the bloc likes to refer to as the “Brussels effect”, where an EU priority on law-making gives it a chance to set the global weather on regulation in strategic areas — such as digital technologies like AI or, indeed, platform power — could exert a growing influence on antitrust enforcements over the pond. Especially if there’s increasing divergence of opportunity being made available on major tech platforms as the DMA drives greater interoperability on Big Tech, and uses data portability mandates as a flywheel for encouraging service switching and multi-homing. (The EU missed a trick on driving messaging interoperability on Apple’s iMessage though, after last month deciding against designating it a DMA core platform service.)

It’s hardly a stretch to say the U.S. is unlikely to be happy to watch its citizens and developers getting less freedom on iPhones than people in Europe. The land of the free won’t like that second class feeling one bit.

EU enforcers have yet to confirm whether Apple’s offer, on Apple Pay, settles their concerns. But they are now engaged in a wider review of its entire DMA compliance plan. Last fall, Apple was designated under the DMA as a so-called “gatekeeper” for iOS, the App Store and its Safari browser. So multiple aspects of how it operates these platforms is under review. Formal investigations may soon follow — with some predicting DMA probes are likely, especially where criticisms persist. (And Apple appears to be the leading contender among the six designated gatekeepers for attracting claims of “malicious compliance” so far, followed by Meta and Google.)

Key here will be what the EU makes of Apple’s decision to respond to the new law by unbundling the fee structure it applies on iOS — applying a new “core tech” fee, as it refers to the new charge it levies on apps that opt into its DMA-amended T&Cs (charged at €0.50 for each first annual install per year over a 1 million threshold for apps distributed outside its App Store).

If you look at the text of the DMA it does not explicitly regulate gatekeeper pricing. Nor are in-scope app store operators literally banned from charging fees. But they do need to comply with the regulation’s requirement to apply FRAND terms (fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory) on business users.

What that means for compliance in the case of Apple’s bid to compensate for (forced) reductions in its usual platform take, i.e. as a result of being required to open up in ways that will enable developers to avoid its App Store fees, by devising a new fee it claims reflects the value developers get from access to its technologies remains to be seen.

A coalition of Apple critics, including Spotify and Epic Games, are continuing to lobby loudly against Apple’s gambit.

In an open letter at the start of this month they suggested the new fee was designed to act as a deterrent, arguing it will prevent developers from even signing up to Apple’s revised T&Cs (which they have to to tap into the DMA entitlements, per Apple’s rule revisions). “Apple’s new terms not only disregard both the spirit and letter of the law, but if left unchanged, make a mockery of the DMA and the considerable efforts by the European Commission and EU institutions to make digital markets competitive,” they fumed.

The EU is sounding sympathetic to this concern. In remarks to Reuters earlier this week, Vestager fired another shot across Apple’s bows — saying she was taking “a keen interest” in its new fee structure — and in the risk that it “will de facto not make it in any way attractive to use the benefits of the DMA”, as she put it. She added that this is “the kind of thing” the Commission will be investigating.

Behind the scenes Commission enforcers may well already be applying pressure on Apple to drop the fee. Although it’s notable that — so far — it hasn’t budged.

Whereas it has made a bunch of concessions in other areas related to DMA compliance, sometimes under public EU pressure. This includes reversing a decision to block progressive web apps (PWAs) in Europe (albeit, this always looked like a counter/retaliatory move/temper-tantrum in response to DMA requirements to open up to non-WebKit browser engines); making a few criteria concessions following developer complaints; reversing a decision to terminate Epic Games’ developer account; and announcing it will allow sideloading of apps in the coming weeks/months, after its initial proposal took a narrower interpretation of the law’s requirements there.

A cynic might suggest this is all part of Apple’s game-plan for avoiding damage to its core iOS business model by tossing the enforcers a few bones in the hopes they’ll be satisfied it’s done enough.

Certainly, it seems unlikely Apple will voluntarily abandon the new core fee. It’s also unlikely the usual suspect developers will stop screaming about unfair Apple fees. So it will probably fall to the Commission to wade in, investigate and formally lay down the law in this area. That is, after all, the task the bloc has set itself.

While the DOJ’s complaint against Apple mainly focuses on a few distinct areas — such as restrictions imposed on super apps, mobile cloud streaming, cross-platform messaging, payment tech and third party smartwatches — it isn’t silent on fees. In the filing it links Apple’s “shapeshifting rules and restrictions” to an ability to “extract higher fees”, in addition to a range of other competition-chilling effects. The DOJ also lists one of the aims of its case as “reducing fees for developers”.

If the EU ends up ordering Apple to ditch its unbundled core tech fee it could pass the baton back to U.S. antitrust enforcers to dial up their own focus on Apple’s fees.

The Commission could move quickly here, too. EU officials have talked in terms of DMA enforcement timescales being a matter of “days, weeks and months”. So corrective action should not take years (but absolutely expect the inevitable legal appeals to grind through the courts at the slower cadence).

On the opening of a non-compliance probe, the DMA allows up to 12 months for the market investigation, with up to six months for reporting preliminary conclusions. Within that time-frame in play — and given the whole raison d’être of the regulation is about empowering EU enforcers to come with faster and more effective interventions — it’s possible that a draft verdict on the legality of Apple’s core tech fee could be pronounced later this year, if the EU moves at pace to open an investigation.

The DMA also furnishes the Commission with interim measures powers, giving enforcers the ability to act ahead of formal non-compliance findings — if they believe there’s “urgency due to the risk of serious and irreparable damage for business users or end users of gatekeepers”.

So, again, 2024 could deliver a lot more antitrust pain for Apple. (Reminder: Penalties for infringements of the DMA can scale up to 10% of global annual turnover or 20% for repeat offences.)

Elsewhere in Europe, German competition authorities designed the iPhone maker as subject to their own domestic ex ante competition reform back in April 2023 — a status that applies on its business in that market until at least 2028. And already, since mid 2022, the German authority has been examining Apple’s requirement that third party apps obtain permission for tracking. So the Federal Cartel Office could force changes on Apple’s practices there in the near term if they conclude it’s harming competition.

In recent years, the iPhone maker has also had to respond to antitrust restrictions in South Korea on its in-app payment commissions after the country passed a 2021 law targeting app store restrictions. Antitrust authorities in India have also been investigating Apple’s practices in this area, since late 2021.

Looking a little further ahead, antitrust trouble looks to be brewing for Apple in the U.K., too, where the competition watchdog have spent years scrutinizing how it operates its mobile app store — concluding in a final report in mid 2022 that there are substantive concerns. The U.K. Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has since moved on to probes of Apple’s restrictions on mobile web browsers and cloud gaming, which remain ongoing.

Almost a year ago the U.K. government announced it would press ahead with its own, long-planned ex ante competition reform, too. This future law will mean the CMA’s Digital Markets Unit will be able to proactively apply bespoke rules on tech giants with so called “strategic market status”, rather than enforcers having to first undertake a long investigation to prove abuse.

Apple is all but certain to fall in scope of the planned U.K. regime — so regional restrictions on its business look sure to keep dialling up.

The planned U.K. law may mirror elements of the EU’s DMA, as the CMA has suggested it could be used to ban self preferencing, enforce interoperability and data access/functionality requirements, and set fairness mandates for business terms. But the U.K. regime is not a carbon copy of the EU approach and looks set to give domestic enforcers more leeway to tailor interventions per platform. Which means there’s a prospect of an even tighter operational straightjacket being applied to Apple’s U.K. business in the years ahead. And zero prospect of a let up in the workload for Apple’s in-house lawyers.

UK’s digital markets regulator gives flavor of rebooted rules coming for Big Tech