Your phone’s camera is as much software as it is hardware, and Glass is hoping to improve both. But while its wild anamorphic lens creeps to market, the company (running on $9.3 million in new money) has released an AI-powered camera upgrade that it says vastly improves image quality — without any weird AI upscaling artifacts.

GlassAI is a purely software approach to improving images, what they call a neural image signal processor (ISP). ISPs are basically what take the raw sensor output — often flat, noisy and distorted — and turn that into the sharp, colorful images we see.

The ISP is also increasingly complex, as phone makers like Apple and Google like to show, synthesizing multiple exposures, quickly detecting and sharpening faces, adjusting for tiny movements, and so on. And while many include some form of machine learning or AI, they have to be careful: Using AI to generate detail can produce hallucinations or artifacts as the system tries to create visual information where none exists. Such “super-resolution” models are useful in their place, but they have to be carefully monitored.

Glass makes both a full camera system based on an unusual lozenge-shaped front element, and an ISP to back it up. And while the former is working toward market presence with some upcoming devices, the latter is, it turns out, a product worth selling in its own right.

Glass rethinks the smartphone camera through an old-school cinema lens

“Our restoration networks correct optical aberrations and sensor issues while efficiently removing noise, and outperform traditional Image Signal Processing pipelines at fine texture recovery,” explained CTO and co-founder Tom Bishop in their news release.

The word “recovery” is key, because details are not simply created but extracted from raw imagery. Depending on how your camera stack already works, you may know that certain artifacts or angles or noise patterns can be reliably resolved or even taken advantage of. Learning how to turn these implied details into real ones — or combining details from multiple exposures — is a big part of any computational photography stack. Co-founder and CEO Ziv Attar says their neural ISP is better than any in the industry.

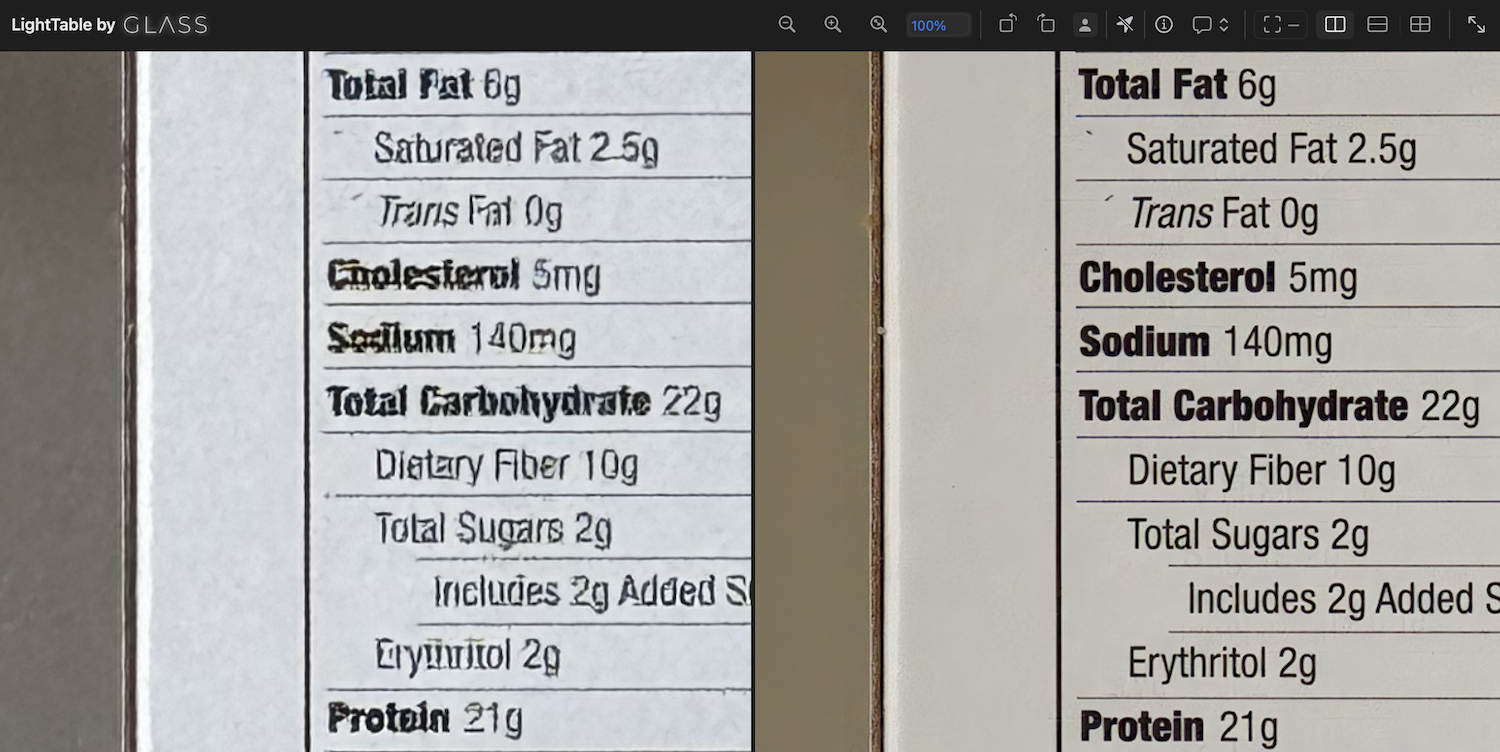

Even Apple, he pointed out, doesn’t have a full neural image stack, only using it in specific circumstances where it’s needed, and their results (in his opinion) aren’t great. He provided an example of Apple’s neural ISP failing to interpret text correctly, with Glass faring much better:

“I think it’s fair to assume that if Apple hasn’t managed to get decent results, it is a hard problem to solve,” he said. “It’s less about the actual stack but more about how you train. We have a very unique way of doing it, which was developed for the anamorphic lens systems and is efficient at any camera. Basically, we have training labs that involve robotics systems and optical calibration systems that manage to train a network to characterize the aberration of lenses in a very comprehensive way, and fundamentally reversing any optical distortion.”

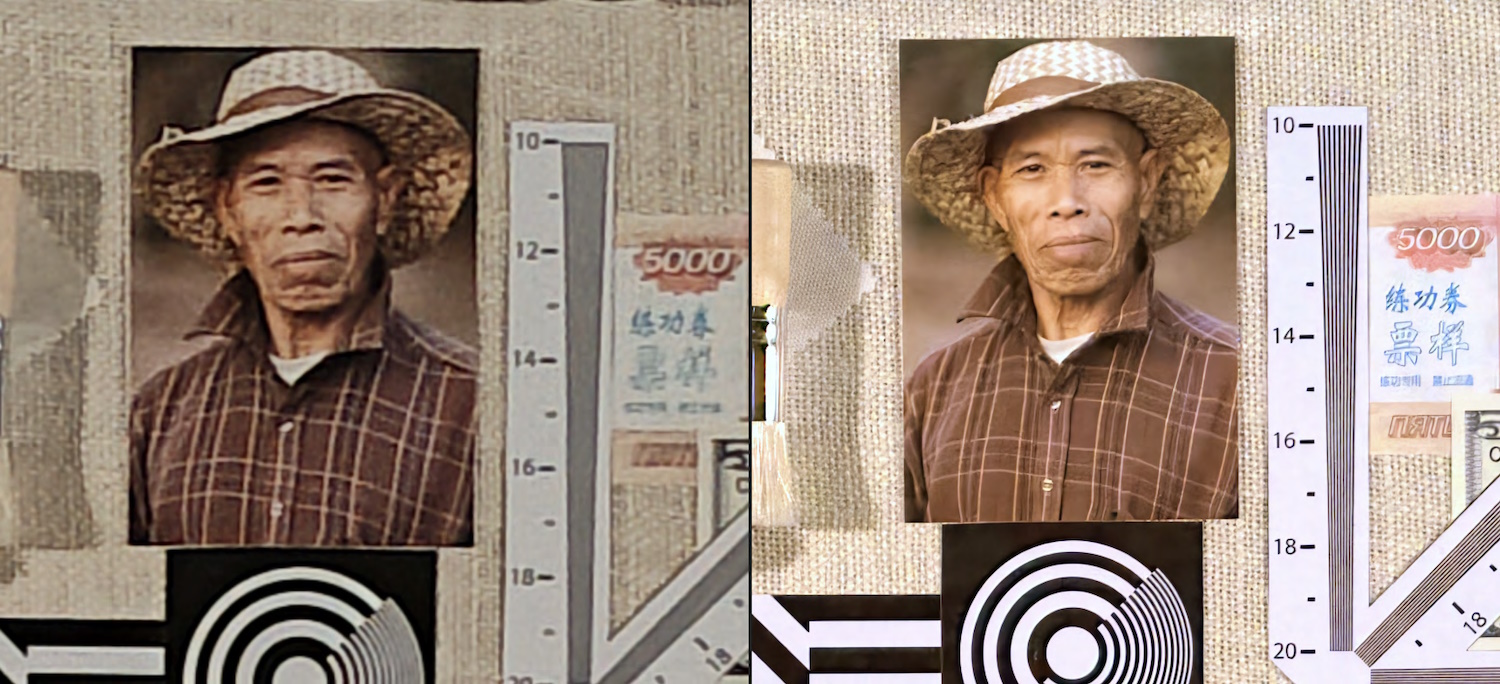

As an example, he provided a case study where they had DXO evaluate the camera on a Moto Edge 40, then do so again with GlassAI installed. The Glass-processed images are all clearly improved, sometimes dramatically so.

At low light levels the built-in ISP struggles to differentiate fine lines, textures and facial details in its night mode. Using GlassAI, it’s as sharp as a tack even with half the exposure time.

You can go peep the pixels on a few test photos Glass has available by switching between the raws and the finals.

Companies putting together phones and cameras have to spend a lot of time tuning the ISP so that the sensor, lens and other bits and pieces all work together properly to make the best image possible. It seems, however, that Glass’s one-size-fits-all process might do a better job in a fraction of the time.

“The time it takes us to train shippable software from the time we put our hands on a new type of device… it varies between few hours to few days. For reference, phone makers spend months tuning for image quality, with huge teams. Our process is fully automated so we can support multiple devices in a few days,” said Attar.

The neural ISP is also end-to-end, meaning in this context that it goes straight from sensor RAW to final image with no extra processes like denoising, sharpening and so on needed.

When I asked, Attar was careful to differentiate their work from super-resolution AI services, which take a finished image and upscale it. These often aren’t “recovering” details so much as inventing them where it seems appropriate, a process that can sometimes produce undesirable results. Though Glass uses AI, it isn’t generative the way many image-related AIs are.

Today marks the product’s availability at large, presumably after a lengthy testing period with partners. If you make an Android phone, it might be good to at least give it a shot.

On the hardware side, the phone with the weird lozenge-shaped anamorphic camera will have to wait until that manufacturer is ready to go public, though.

While Glass develops its tech and is trying out customers, it’s also been busy scaring up funding. The company just closed a $9.3 million “extended seed,” which I put in quotes because the seed round was in 2021. The new funding was led by GV, with Future Ventures, Abstract Ventures and LDV Capital participating.