The EU Digital Identity Wallet is an ambitious project by the European Union that’s still a bit under the radar but worth paying attention to, as it could deliver big things in the next few years.

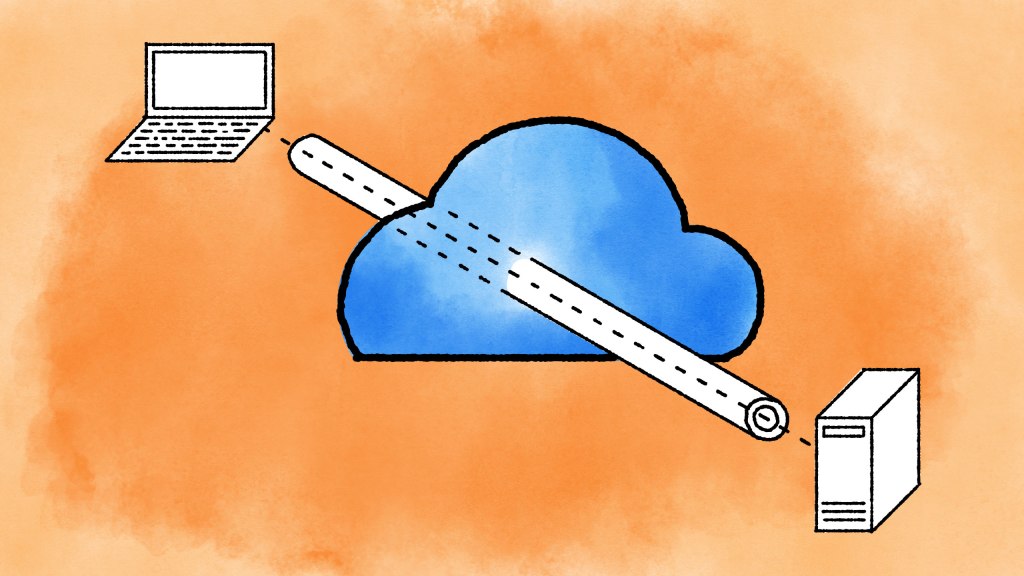

The goal is to set up a universal digital identity system for citizens. If all goes to plan, Europeans will be able to download and use a free EU Digital Identity Wallet to access a wide range of public and private services, relying on identity verification and authentication of other credentials stored in an app on their smartphone.

Following recent adoption of a key legal framework, EU countries are expected to issue the first of EU Digital Identity Wallets by the end of 2026. Unlike current national e-ID schemes, the future Pan-EU wallets will be recognized by all member states.

While national e-ID systems have been available in some European countries for many years — Estonia is a particular pioneer in digital identity — regional lawmakers have, since 2021, set themselves the goal of creating conditions for a digital identity system that works across the bloc’s single market.

So while there won’t be a single, universal EU wallet app for everyone to use, the goal is to establish a system where different wallet apps will work anywhere in the EU, aligning with the bloc’s Digital Single Market mission.

An EU digital ID wallet for everything?

One obvious motivation for setting up the EU Digital Identity Wallet is convenience.

Europeans will be able to download a wallet app to their smartphone or device and use it to store and selectively share key credentials when they need to do things like verify their identity or prove their age. The wallet will work both for ID checks online and in the real world. It’s also intended as a digital repository for official documents, such as a driver’s license, medical prescriptions, educational qualifications, passports, etc. E-signing functionality will also be supported.

So less hassle managing different bits of paper, or even remembering where you put your bank cards, is the general idea.

But there are other more strategic motivating factors in play. The bloc has woken up to the value of data in our fast-accelerating AI age. Policies that remove friction and grease the flow of information — or at least try to when it comes to getting citizens to share personal data to do things like sign up for new services or to transact — fit the political game plan.

The EU has an extensive and growing body of digital regulation. A Pan-EU e-ID would clearly come in very handy here. For example, aspects of the online governance regime established by the Digital Services Act (DSA) could be easier to implement once the EU can point to having a “universal, secure and trustworthy” digital ID system in place, as the EU Digital Identity Wallet is being billed. Think privacy-preserving access to adult content websites for people who could use the digital ID to verify they’re over 18, for example.

Another big EU digital policy push in recent years aims to remove barriers to the sharing and reuse of data, including across internal borders, by setting up infrastructure and rules for so-called Common European Data Spaces. Again, a universal EU digital ID that promises citizens privacy and autonomy could make Europeans more comfortable doing more info-sharing — helping data flow into these strategic spaces.

Interestingly, though, the EU’s president, Ursula von der Leyen, opted for a very different framing for the opportunity for the wallet when announcing the plan in her September 2020 State of the Union address, pointing to growing privacy risks for citizens who are constantly being asked to share data in order to access online services. The wallet responds to this concern because a core feature is support for selective data sharing. So in addition to an EU pledge that use of the wallet will remain voluntary for citizens, the main pitch to users is that it’s “privacy-preserving” as they get to remain in control: selecting which data they share with whom.

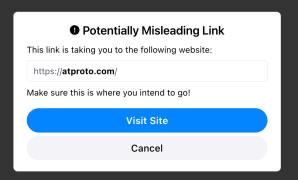

Having a privacy-preserving approach could help the EU unlock finer-grained digital regulation opportunities, too, though. As noted above, it could give citizens a means to share their verified age but not their identity, allowing a wallet app user to sign into an age-restricted service anonymously. The EU wants the wallets to support wider governance goals under the DSA, which look set to usher in harder age verification requirements for services with content that might be inappropriate for kids — that is, once the appropriate “privacy preserving” tech exists.

Other use cases for the wallet that the EU has discussed include an apartment-rental scenario where a citizen could share a bunch of verified intel about their rental history with a potential landlord without having to confirm their identity unless/until they get to sign the contract. Or someone with multiple bank accounts around the Union could use it to simplify transaction authorizations.

Online services will be obliged to accept the Pan-EU credential. So it’s also being pitched as a European alternative to existing (commercial) digital identity offerings, such as the “sign in with” credentials offered by Big Tech players, like Apple and Google.

Challenging Big Tech’s grip on data

Here the bloc’s lawmakers look to be responding to concerns about how much power has been ceded to platform giants on account of the key digital infrastructure they own and operate.

It’s no surprise the EU Digital Identity Wallet proposal was adopted by the Commission in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, when apps that could display a person’s COVID-19 vaccination status were on everyone’s mind. But the public health crisis also starkly underscored an asymmetrical power dynamic between lawmakers and the commercial giants controlling mainstream mobile technology infrastructure. (Apple and Google literally set rules on how COVID-19 exposure notification data could be exchanged, with their technical choices overriding governments’ directly stated preferences in several cases.)

Beyond considerations of strategic digital sovereignty, a universal e-ID wallet concept ties tightly to the EU’s general push to amp up digitalization as a flywheel for better economic fortunes. Assuming the system is well-executed and reliable, and the wallets themselves are user friendly and easy to use, a universal EU ID could boost productivity by increasing efficiency and uptake of online services.

Of course, that’s a big “if”; there are sizable technical challenges to delivering on the EU vision for the universal ID system.

Security and privacy are obviously essential pieces of the puzzle. The first is fundamental for any identity and authentication system to fly. The second comprises the bloc’s main pitch to citizens who will need to be persuaded to adopt the wallets if the whole project isn’t to end up an expensive white elephant.

Poor implementation is a clear risk. Low uptake of flaky national e-ID scheme shows what could go wrong. Wallet apps will need to be slick and easy to use across the full sweep of planned use cases, as well as having robust security and privacy — which demands a whole ecosystem of players get behind the project — or users simply won’t get on board.

Remember, competition on digital identity is coming from already baked-in mainstream platform offerings, like “Sign in with Google.” And, sadly, convenience and ease-of-use still often trump privacy concerns in the online arena.

Privacy could also create barriers to adoption. After the proposal was unveiled, there were some reservations expressed about the EU setting up a universal ID infrastructure, with some commentators invoking the risk of function-creep toward a China-style social control. Having a credible technical architecture that both secures and firewalls citizens’ data will therefore be critical to success.

Universal availability by 2030

Getting the EU Digital Identity Wallet system off the ground has already involved years of preparatory work, but there’s plenty more testing, standard setting and implementation ahead.

So far the bloc has put in place a legal framework for interoperable EU wallets (i.e., the Digital Identity Regulation, which entered into force in May this year). Work on the development of a secure technical architecture, common standards and specifications is ongoing, but a common EU Toolbox has been established. The Commission has also published an architecture reference on GitHub. Code is being open sourced, and the EU intends ecosystem infrastructure to be based on common standards to drive trust and adoption.

The bloc is also engaged with industry and public sector stakeholders on large-scale pilots to test the proposed technical specifications.

More paving needs to be laid in the coming years, including through a series of implementing acts affirming critical technical details. Plenty could still go wrong. But the EU has at least given itself a fairly generous lead-in to get this one right. So while the first wallets are supposed to be coming online in a couple years’ time, the bloc is not expecting universal system access for its circa 450 million citizens until 2030.

Europe wants to go its own way on digital identity