The U.S. Federal Trade Commission has banned the data broker X-Mode Social from sharing or selling users’ sensitive location data, the federal regulator said Tuesday.

The first of its kind settlement prohibits X-Mode, now known as Outlogic, from sharing and selling users’ sensitive information to others. The settlement will also require the data broker to delete or destroy all the location data it previously collected, along with any products produced from this data, unless the company obtains consumer consent or ensures the data has been de-identified.

X-Mode buys and sells access to the location data collected from ordinary phone apps. While just one of many organizations in the multibillion-dollar data broker industry, X-Mode faced scrutiny for selling access to the commercial location data of Americans’ past movements to the U.S. government and military contractors.

Soon after, Apple and Google told developers to remove X-Mode from their apps or face a ban from the app stores.

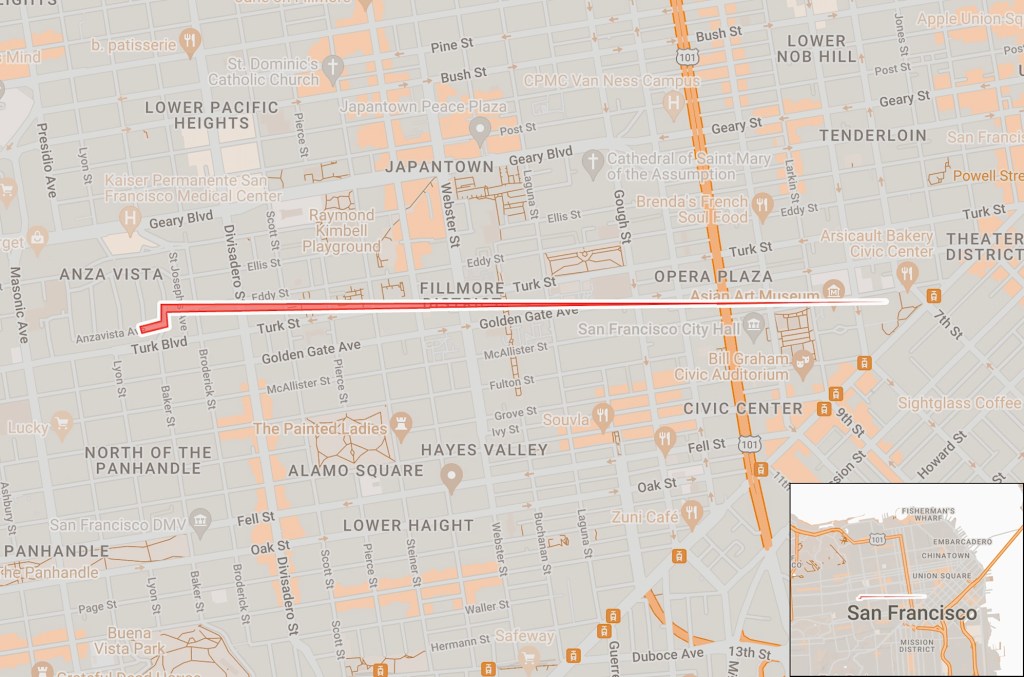

The FTC alleged that X-Mode sold precise location data that could be used to track people’s visits to sensitive locations, such as medical and reproductive health clinics, places of religious worship and domestic abuse shelters.

The regulator also alleged that the data broker failed to remove the sensitive locations from the raw location data it sold to third-parties and did not implement “reasonable or appropriate safeguards” against downstream use of this precise location data. For at least one of its contracts, the FTC said that X-Mode provided an unnamed private clinical research company with information about consumers who had visited certain medical facilities, pharmacies or specialty infusion centers within a geographic area across Columbus, Ohio.

X-Mode also failed to ensure that users of its own apps — Drunk Mode and Walk Against Humanity — were fully informed about how their precise location data would be used, the FTC said.

“The information revealed through the location data that X-Mode/Outlogic sold not only violated consumers’ privacy but also exposed them to potential discrimination, physical violence, emotional distress, and other harms,” the FTC said in a statement.

“Geolocation data can reveal not just where a person lives and whom they spend time with but also, for example, which medical treatments they seek and where they worship,” said FTC chair Lina M. Khan. “The FTC’s action against X-Mode makes clear that businesses do not have free license to market and sell Americans’ sensitive location data.”

“By securing a first-ever ban on the use and sale of sensitive location data, the FTC is continuing its critical work to protect Americans from intrusive data brokers and unchecked corporate surveillance,” said Khan.

As per the FTC’s order, X-Mode must also implement procedures to ensure that recipients of its location data do not associate the data with locations that provide services to LGBTQIA+ people, provide a simple way for consumers to withdraw their consent for the collection and use of their location data and establish and implement a comprehensive privacy program that protects the privacy of consumers’ personal information.

A statement given to TechCrunch by public relations firm Broadsheet, which represents Outlogic, reads: “We disagree with the implications of the FTC press release. After a lengthy investigation, the FTC found no instance of misuse of any data and made no such allegation. Since its inception, X-Mode has imposed strict contractual terms on all data customers prohibiting them from associating its data with sensitive locations such as healthcare facilities. Adherence to the FTC’s newly introduced policy will be ensured by implementing additional technical processes and will not require any significant changes to business or products.”

Sen. Ron Wyden, whose office first revealed that X-Mode had sold location data to U.S. military contractors, said in response to the FTC’s findings: “I commend the FTC for taking tough action to hold this shady location data broker responsible for its sale of Americans’ location data.”

Updated with comment from Outlogic and Ron Wyden’s office.

Location broker X-Mode continues to track users despite app store bans