Trending News

17 October, 2024

6.96°C New York

Even as quick commerce startups are retreating, consolidating or shutting down in many parts of the world, the model is showing encouraging signs in India. Consumers in urban cities are embracing the convenience of having groceries delivered to their doorstep in just 10 minutes. The companies making those deliveries — Blinkit, Zepto and Swiggy’s Instamart — are already charting a path to profitability.

Analysts are intrigued by the potential of 10-minute deliveries to disrupt e-commerce. Goldman Sachs recently estimated that Blinkit, which Zomato acquired in 2022 for less than $600 million, is already more valuable than its decacorn food delivery parent firm.

As of earlier this year, Blinkit held a 40% share of the quick commerce market, with Swiggy’s Instamart and Zepto close behind, according to HSBC. Flipkart, owned by Walmart, plans to enter the quick commerce space as soon as next month, further validating the industry’s potential.

Investors are also showing strong interest in the sector. Zomato boasts a valuation of $19.7 billion despite minimal profitability, processing around 3 million orders a day. In comparison, Chinese giant Meituan, which processes more than 25 times as many orders daily, has a market cap of $93 billion. Zepto, which achieved unicorn status less than a year ago, is finalizing new funding at a valuation exceeding $3 billion, according to people familiar with the matter.

Consumers are buying the quick commerce convenience, too. According to a recent Bernstein survey, the adoption was highest among millennials aged 18 to 35, with 60% of those in the 18 to 25 age bracket preferring quick commerce platforms over other channels. Even the 36+ age group is adopting digital channels, with over 30% preferring quick commerce.

While India’s rapid urbanization makes it a prime target for quick commerce, the industry’s unique operational model and infrastructure needs could limit its long-term growth and profitability. As competition intensifies, the impact of quick commerce is likely to be felt more acutely by India’s e-commerce giants. But what makes India’s retail market so attractive for quick commerce players, and what challenges lie ahead?

India’s e-commerce sales stood at $60 billion to $65 billion last year, according to industry estimates. That’s less than half of the sales generated by e-commerce firms on China’s last Singles Day and represents less than 7% of India’s overall retail market of more than $1 trillion.

Reliance Retail, India’s largest retail chain, clocked a revenue of about $36.7 billion in the financial year ending in March, with a valuation standing at $100 billion. The unorganized retail sector — the neighborhood stores (popularly known as kirana) that dot thousands of Indian cities, towns and villages — continues to dominate the market.

“The market is huge and, on paper, ripe for disruption. Nothing done so far has made a material dent in the industry. This is why any time a new model shows signs of functioning, all stakeholders shower them with love,” said a seasoned entrepreneur who helped build the supply chain for one of the leading retail ventures.

In other words, there’s no shortage of room for growth.

One of the factors behind the quick commerce’s fast adoption is the similarity it has with the kirana model that has worked in India for decades. Quick commerce firms have devised a new supply chain system, setting up hundreds of unassuming warehouses, or “dark stores,” strategically situated within kilometers of residential and business areas from where large numbers of orders are placed. This allows the firms to make deliveries within minutes of order purchase.

This approach differs from that of e-commerce players like Amazon and Flipkart, which have fewer but much larger warehouses in a city, generally situated in localities where rent is cheaper and farther from residential areas.

The unique characteristics of Indian households further contribute to the appeal of quick commerce. Indian kitchens typically stock a higher number of SKUs compared to their Western counterparts, necessitating frequent top-up purchases that are better serviced by local stores and quick commerce rather than modern retail. Additionally, limited storage space in most Indian homes makes monthly bulk grocery shopping less practical, and customers tend to favor fresh food purchases, which quick commerce can easily accommodate.

According to Bernstein, quick commerce platforms can price products 10% to 15% cheaper than mom-and-pop stores while maintaining about 15% gross margins due to the removal of intermediaries. Quick commerce dark stores have rapidly expanded their SKU count from 2,000 to 6,000, with plans to further increase it to 10,000 to 12,000. These stores are replenishing their stocks two to three times a day, according to store managers.

Zepto, Blinkit and Swiggy’s Instamart are increasingly expanding beyond the grocery category, selling a variety of items, including clothing, toys, jewelry, skincare products and electronics. A TechCrunch analysis finds that the majority of items listed by Amazon India in its bestsellers list are available on quick commerce platforms.

Quick commerce has also become an important distribution channel for major food brands in India. Consumer goods giant Dabur India expects quick commerce to drive 25% to 30% of the company’s sales. Hindustan Unilever, the Indian arm of the U.K.’s Unilever, has identified quick commerce as an “opportunity we will not let go.” And for Nestle India, “Blinkit is becoming as important as Amazon.”

While quick commerce doesn’t need to expand beyond the grocery category, which itself is more than a half-trillion-dollar market in India, their expansion into electronics and fashion is likely to be limited. Electronics drive 40% to 50% of all sales on Amazon and Flipkart, according to analyst estimates. If quick commerce can crack this market, it will pose a significant and direct challenge to e-commerce giants. Goldman Sachs estimates that the total addressable market in grocery and non-grocery for quick commerce companies in the top 40-50 cities is about $150 billion.

However, the sale of smartphones and other high-ticket items is more of a gimmick and not something that can be done at a large scale, according to an e-commerce entrepreneur.

“It doesn’t make any sense. What quick commerce is good at is forward-commerce. But smartphones and other pricey items tend to have a not-so-insignificant return rate.… They don’t have the infrastructure to accommodate the reverse-logistics,” he said, requesting anonymity as he is one of the earliest investors in a leading quick commerce firm.

Quick commerce’s current infrastructure also doesn’t permit the sale of large appliances. This means you cannot purchase a refrigerator, air conditioner, or TV from quick commerce. “But that’s what some of these firms are suggesting, and analysts are lapping it up,” the investor said.

Falguni Nayar, founder of skincare platform Nykaa, highlighted at a recent conference that quick commerce is primarily taking share from kirana stores and would not be able to keep as much inventory and assortment as specialty platforms that educate customers.

The quick commerce story in India remains an urban phenomenon concentrated in the top 25 to 30 cities. Goldman Sachs wrote in a recent analysis that the demand in smaller cities likely makes it difficult for fresh grocery economics to work.

E-commerce giant Flipkart will launch its quick commerce service in limited cities as soon as next month, seeing an opportunity to woo customers of Amazon India. The majority of Flipkart’s customers are in smaller Indian cities and towns.

Amazon — increasingly scaling down on its investments in e-commerce in India — has so far shown no interest in quick commerce in the country. The company, which offers same-day delivery for some items to Prime members, has questioned the quality of products from firms making “fast” deliveries in some of its marketing campaigns.

As brands increasingly focus on quick commerce as their fastest-growing channel and more consumers embrace the convenience and value proposition of 10-minute deliveries, the stage is set for a fierce battle between quick commerce and e-commerce giants in India.

WhatsApp has announced the release of a filter called “Favorites” to let you quickly find chats from the people and groups that matter most and directly connect with them over a call from the top of the calls tab.

The “Favorites” filter started rolling out on Tuesday and will be available to all WhatsApp users in the coming weeks. It lets you keep all the chats from your best friend or family group under one roof for quick access. The instant messaging app has also added a “Favorites” section to the calls tab to speed-dial your favorite contacts without requiring you to go through the recent call logs or find their contact from the contacts book.

To add a contact or group to your favorite list, select the “Favorites” filter from your chats screen or tap the “Add favorite” option after selecting the particular contact or group from the calls tab. You can also add a chat to your favorites by long-tapping it and selecting “Add to favorite.” Similarly, WhatsApp has provided an option to manage your favorite contacts and groups by going to Settings > Favorites > Add to Favorite. You can also reorder them based on your preference at any time.

WhatsApp was spotted testing the feature to select favorite contacts on iOS and the web in February, as reported by WABetaInfo. It also appeared on Android in April.

The latest update comes three months after WhatsApp introduced chat filters. The Meta-owned app initially released “All,” “Unread” and “Groups” as the three filters. However, adding “Favorites” makes chat filters even more useful as people relied on alternative ways to quickly call or video chat with their favorite contacts via WhatsApp in the absence of the native filter.

Zepto has finalized a $340 million round that increases its valuation to $5 billion, up from $3.6 billion in June and $1.4 billion last August, as the startup races to win market share in India’s contested quick commerce market.

General Catalyst and Mars Growth Capital are co-leading the Series G round, according to people familiar with the matter. The round gives Zepto — which gives customers access to a range of categories, from grocery to electronics, that they can receive in minutes — a valuation of $4.6 billion pre-money, so about $5 billion following the funding, according to a term sheet seen by TechCrunch.

Zepto competes with BlinkIt (owned by Zomato) and Swiggy’s Instamart in India’s fast-growing quick commerce market, which is beginning to chip away market share from traditional e-commerce giants.

Zepto is on track to do more than $1.5 billion in annualized sales, according a source familiar with the matter. BlinkIt is currently at about $2 billion annualized GMV. Quick commerce companies, which all started operations just three years ago, will do a combined annual sales of $4.5 billion to $5 billion in India this year, compared to Amazon India’s $18 billion. Amazon has been operating in India for about 10 years and has invested more than $7 billion in its e-commerce business in the country.

Retail is a $1.1 trillion market in India, but much of it remains untapped. Reliance Retail, which operates the nation’s largest retail chain, is valued at about $100 billion. “This is why any time a new model shows semblance of traction in India retail, investors greatly reward it,” an investor told TechCrunch.

Indian outlet Economic Times first reported about Mars Growth’s participation in Zepto’s new round. The Information earlier reported that General Catalyst was engaging with Zepto.

These quick commerce companies have established numerous discreet warehouses, known as “dark stores,” throughout urban India. By strategically locating these facilities within a few miles of high-demand residential and commercial areas, they can fulfill orders within minutes of purchase.

The growth of quick commerce firms in India, a $4 trillion economy, has surprised many investors and analysts, especially because many similar business models collapsed in other markets. This rapid expansion has also caught some established e-commerce players off guard, with analysts suggesting that companies like Amazon have been slow to adapt to changing consumer habits in India.

Amazon hasn’t been “strategic enough. And founders — whether it’s Deepinder (Zomato), Aadit (Zepto), or Vidit (Meesho) or the team at Flipkart — have out-executed the management team [of Amazon],” Bernstein analyst Rahul Malhotra told TechCrunch this month. Flipkart recently launched its quick commerce offering in parts of Bangalore.

Zepto aims to expand its network of dark stores to over 700 by March 2025. The startup, which also counts Nexus, Lightspeed, Avra and StepStone among its backers, said in June that its revenue had risen 140% from a year earlier. It works with more than 50,000 delivery partners and is adding over 5,000 delivery partners each month.

Zepto said earlier that about 75% of its dark stores were EBITDA positive as of last month. Improved efficiency and scale mean that a dark store that previously took 23 months to achieve profitability now reaches that milestone in six months, Zepto said in June.

Zepto currently operates in top Indian cities, and plans to expand to select smaller cities in the coming months.

According to Goldman Sachs, the total addressable market in the grocery and non-grocery categories for quick commerce companies in the top 40-50 cities is about $150 billion.

PayPal said on Tuesday that it is making its quick guest-checkout solution, Fastlane, available to all U.S. merchants after testing it with select businesses for a few months. Businesses will initially have to use the company’s payment processing services, such as PayPal Braintree or PayPal Complete Payments, to use Fastlane.

The company first started testing Fastlane in January. It stores customer data such as their names, email IDs, phone numbers, shipping addresses, and payment details. When a customer is on a merchant’s website, Fastlane can pull all of this data without the customer having to log in. Users just need to enter a verification code they get via email to approve a purchase.

PayPal said it relies on signals like a customer entering their phone number or email to fetch data from Fastlane. If a customer is not signed up for Fastlane, PayPal gives them an option to do so during the checkout.

According to a study published by Capterra, which sells software for marketplaces, 43% of customers prefer checking out their shopping as a “guest” so that they don’t have to sign in to e-commerce websites. And, 72% of consumers said they choose guest checkout even if they have an account.

Frank Keller, EVP of large enterprise and merchant platforms at PayPal, told TechCrunch over a call that Fastlane helps businesses with better conversion.

“If you look at conversion rates of guest checkouts, they are fundamentally lower than merchants get with other methods because you need to fill in all your information. That’s why we built Fastlane to improve the speed of guest checkout, because speed wins sales,” Keller said.

PayPal claims that during the Fastlane test, guest checkout conversions were around 80% and checkouts were 32% faster.

PayPal Fastlane competes with other one-click solutions such as Stripe Link, Checkout.com, OurPass, and Deuna. Keller added that the company plans to offer this service in other regions.

WhatsApp has announced the release of a filter called “Favorites” to let you quickly find chats from the people and groups that matter most and directly connect with them over a call from the top of the calls tab.

The “Favorites” filter started rolling out on Tuesday and will be available to all WhatsApp users in the coming weeks. It lets you keep all the chats from your best friend or family group under one roof for quick access. The instant messaging app has also added a “Favorites” section to the calls tab to speed-dial your favorite contacts without requiring you to go through the recent call logs or find their contact from the contacts book.

To add a contact or group to your favorite list, select the “Favorites” filter from your chats screen or tap the “Add favorite” option after selecting the particular contact or group from the calls tab. You can also add a chat to your favorites by long-tapping it and selecting “Add to favorite.” Similarly, WhatsApp has provided an option to manage your favorite contacts and groups by going to Settings > Favorites > Add to Favorite. You can also reorder them based on your preference at any time.

WhatsApp was spotted testing the feature to select favorite contacts on iOS and the web in February, as reported by WABetaInfo. It also appeared on Android in April.

The latest update comes three months after WhatsApp introduced chat filters. The Meta-owned app initially released “All,” “Unread” and “Groups” as the three filters. However, adding “Favorites” makes chat filters even more useful as people relied on alternative ways to quickly call or video chat with their favorite contacts via WhatsApp in the absence of the native filter.

Even as quick commerce startups are retreating, consolidating or shutting down in many parts of the world, the model is showing encouraging signs in India. Consumers in urban cities are embracing the convenience of having groceries delivered to their doorstep in just 10 minutes. The companies making those deliveries — Blinkit, Zepto and Swiggy’s Instamart — are already charting a path to profitability.

Analysts are intrigued by the potential of 10-minute deliveries to disrupt e-commerce. Goldman Sachs recently estimated that Blinkit, which Zomato acquired in 2022 for less than $600 million, is already more valuable than its decacorn food delivery parent firm.

As of earlier this year, Blinkit held a 40% share of the quick commerce market, with Swiggy’s Instamart and Zepto close behind, according to HSBC. Flipkart, owned by Walmart, plans to enter the quick commerce space as soon as next month, further validating the industry’s potential.

Investors are also showing strong interest in the sector. Zomato boasts a valuation of $19.7 billion despite minimal profitability, processing around 3 million orders a day. In comparison, Chinese giant Meituan, which processes more than 25 times as many orders daily, has a market cap of $93 billion. Zepto, which achieved unicorn status less than a year ago, is finalizing new funding at a valuation exceeding $3 billion, according to people familiar with the matter.

Consumers are buying the quick commerce convenience, too. According to a recent Bernstein survey, the adoption was highest among millennials aged 18 to 35, with 60% of those in the 18 to 25 age bracket preferring quick commerce platforms over other channels. Even the 36+ age group is adopting digital channels, with over 30% preferring quick commerce.

While India’s rapid urbanization makes it a prime target for quick commerce, the industry’s unique operational model and infrastructure needs could limit its long-term growth and profitability. As competition intensifies, the impact of quick commerce is likely to be felt more acutely by India’s e-commerce giants. But what makes India’s retail market so attractive for quick commerce players, and what challenges lie ahead?

India’s e-commerce sales stood at $60 billion to $65 billion last year, according to industry estimates. That’s less than half of the sales generated by e-commerce firms on China’s last Singles Day and represents less than 7% of India’s overall retail market of more than $1 trillion.

Reliance Retail, India’s largest retail chain, clocked a revenue of about $36.7 billion in the financial year ending in March, with a valuation standing at $100 billion. The unorganized retail sector — the neighborhood stores (popularly known as kirana) that dot thousands of Indian cities, towns and villages — continues to dominate the market.

“The market is huge and, on paper, ripe for disruption. Nothing done so far has made a material dent in the industry. This is why any time a new model shows signs of functioning, all stakeholders shower them with love,” said a seasoned entrepreneur who helped build the supply chain for one of the leading retail ventures.

In other words, there’s no shortage of room for growth.

Quick commerce firms are borrowing many traits from kirana stores to make themselves relevant to Indian consumers. They have devised a new supply chain system, setting up hundreds of unassuming warehouses, or “dark stores,” strategically situated within kilometers of residential and business areas from where large numbers of orders are placed. This allows the firms to make deliveries within minutes of order purchase.

This approach differs from that of e-commerce players like Amazon and Flipkart, which have fewer but much larger warehouses in a city, generally situated in localities where rent is cheaper and farther from residential areas.

The unique characteristics of Indian households further contribute to the appeal of quick commerce. Indian kitchens typically stock a higher number of SKUs compared to their Western counterparts, necessitating frequent top-up purchases that are better serviced by local stores and quick commerce rather than modern retail. Additionally, limited storage space in most Indian homes makes monthly bulk grocery shopping less practical, and customers tend to favor fresh food purchases, which quick commerce can easily accommodate.

According to Bernstein, quick commerce platforms can price products 10% to 15% cheaper than mom-and-pop stores while maintaining about 15% gross margins due to the removal of intermediaries. Quick commerce dark stores have rapidly expanded their SKU count from 2,000 to 6,000, with plans to further increase it to 10,000 to 12,000. These stores are replenishing their stocks two to three times a day, according to store managers.

Zepto, Blinkit and Swiggy’s Instamart are increasingly expanding beyond the grocery category, selling a variety of items, including clothing, toys, jewelry, skincare products and electronics. A TechCrunch analysis finds that the majority of items listed by Amazon India in its bestsellers list are available on quick commerce platforms.

Quick commerce has also become an important distribution channel for major food brands in India. Consumer goods giant Dabur India expects quick commerce to drive 25% to 30% of the company’s sales. Hindustan Unilever, the Indian arm of the U.K.’s Unilever, has identified quick commerce as an “opportunity we will not let go.” And for Nestle India, “Blinkit is becoming as important as Amazon.”

While quick commerce doesn’t need to expand beyond the grocery category, which itself is more than a half-trillion-dollar market in India, their expansion into electronics and fashion is likely to be limited. Electronics drive 40% to 50% of all sales on Amazon and Flipkart, according to analyst estimates. If quick commerce can crack this market, it will pose a significant and direct challenge to e-commerce giants. Goldman Sachs estimates that the total addressable market in grocery and non-grocery for quick commerce companies in the top 40-50 cities is about $150 billion.

However, the sale of smartphones and other high-ticket items is more of a gimmick and not something that can be done at a large scale, according to an e-commerce entrepreneur.

“It doesn’t make any sense. What quick commerce is good at is forward-commerce. But smartphones and other pricey items tend to have a not-so-insignificant return rate.… They don’t have the infrastructure to accommodate the reverse-logistics,” he said, requesting anonymity as he is one of the earliest investors in a leading quick commerce firm.

Quick commerce’s current infrastructure also doesn’t permit the sale of large appliances. This means you cannot purchase a refrigerator, air conditioner, or TV from quick commerce. “But that’s what some of these firms are suggesting, and analysts are lapping it up,” the investor said.

Falguni Nayar, founder of skincare platform Nykaa, highlighted at a recent conference that quick commerce is primarily taking share from kirana stores and would not be able to keep as much inventory and assortment as specialty platforms that educate customers.

The quick commerce story in India remains an urban phenomenon concentrated in the top 25 to 30 cities. Goldman Sachs wrote in a recent analysis that the demand in smaller cities likely makes it difficult for fresh grocery economics to work.

E-commerce giant Flipkart will launch its quick commerce service in limited cities as soon as next month, seeing an opportunity to woo customers of Amazon India. The majority of Flipkart’s customers are in smaller Indian cities and towns.

Amazon — increasingly scaling down on its investments in e-commerce in India — has so far shown no interest in quick commerce in the country. The company, which offers same-day delivery for some items to Prime members, has questioned the quality of products from firms making “fast” deliveries in some of its marketing campaigns.

As brands increasingly focus on quick commerce as their fastest-growing channel and more consumers embrace the convenience and value proposition of 10-minute deliveries, the stage is set for a fierce battle between quick commerce and e-commerce giants in India.

Even as quick commerce is slowly fading in many markets and several heavily funded startups have folded shop in the past two years, India is emerging as a striking outlier where the model — of delivering items to customers in 10 to 20 minutes — appears to be working.

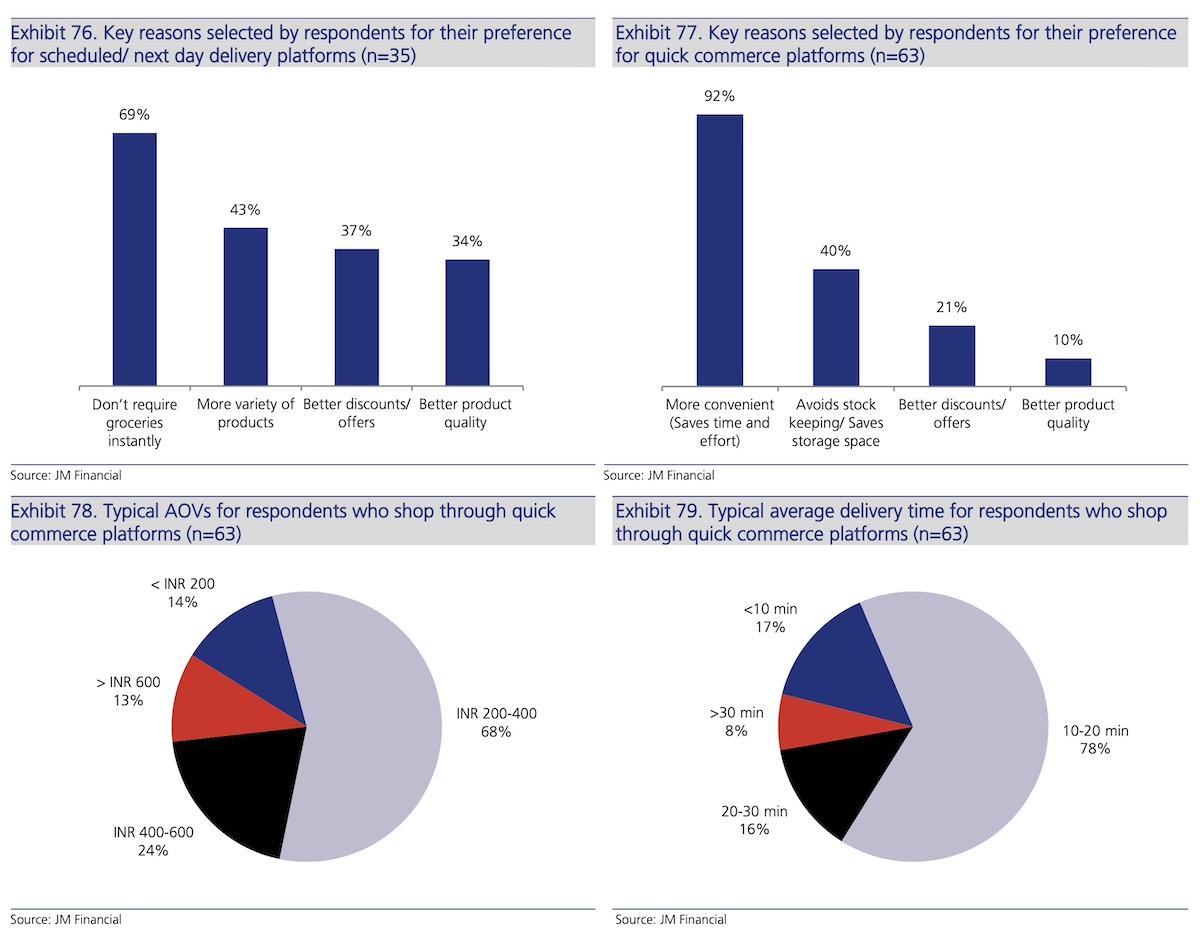

India’s quick commerce market has witnessed a staggering tenfold growth between 2021 and 2023, fueled by the sector’s ability to cater to the distinct needs of urban consumers seeking convenience for unplanned, small-ticket purchases. Despite this rapid expansion, however, quick commerce has only captured a modest 7% of the potential market, with a total addressable market (TAM) estimated at $45 billion, surpassing that of food delivery, according to JM Financial.

The quick commerce players — Zomato-owned Blinkit, Swiggy’s Instamart and YC Continuity-backed Zepto — can reach an estimated 25 million households, who are likely to spend an average of 4,000 to 5,000 rupees ($48 to $60) per month, according to Bank of America.

The top players are expected to expand their reach to 45 to 55 cities within the next 3 to 5 years, up from the current 25 cities, BofA added. Regular customers of quick commerce platforms typically order three to four times per month, with retention rates as high as 60% to 65%. Top users, however, make even more frequent transactions, ranging from 30 to 40 times per month, BofA analysts wrote in a note Monday.

“Quick commerce model had its own challenges in Europe and USA but in India, especially in top markets, product-market fit development was led by users liking the experience when things are delivered faster to them at doorstep,” the analysts wrote. “These users don’t want to go back to local corner stores and spend 10 to 15 minutes/fuel extra. The usage started from top cities like Bengaluru, Delhi-NCR, Kolkata etc and then has moved to even smaller cities like Indore, Pune, Rajkot etc.”

Zomato’s Blinkit leads the quick commerce market in India, having cornered as much as 46% of the market share by GMV in the quarter that ended in December, according to a separate analysis.

Swiggy’s Instamart follows with a 27% share; newcomer Zepto has quickly gained ground, securing 21% of the market; and Bigbasket’s BB Now trails with a 7% share, brokerage firm JM Financial said. Reliance Retail–backed Dunzo, which pioneered the quick commerce model in India, has virtually ceded its entire market share to competition.

“With more than 10 active players, the space was very competitive a couple of years back,” JM Financial wrote of the quick commerce market in a recent note. “It appeared that an intense phase of multi-year cash-burn would soon follow. However, contrary to expectations, several players including some well-funded ones folded early in their endeavour. While some faced funding challenges, a few others were affected by structural issues such as lack of product market fit, inability to solve the hyperlocal complexity, inability to build a robust end-to-end supply chain and … failure to create a strong brand recall.”

As quick commerce players vie for a larger slice of the market, the success of their ventures hinges on the development of efficient supply chains. Companies are making substantial investments in dark store operations, streamlining inventory management and establishing direct partnerships with FMCG manufacturers and farmers. By circumventing traditional distribution channels, these firms aim to enhance product quality, expedite delivery times, and boost overall operational efficiency, industry analysts said.

Dark stores, the backbone of quick commerce operations, have significantly expanded their product offerings, now carrying over 6,000 SKUs per store, a substantial increase from the 2,000 to 4,000 SKUs they housed just a few years ago. In contrast, traditional neighborhood kirana stores, which are ubiquitous across Indian cities, towns, and villages, typically stock between 1,000 and 1,500 items, according to JM Financial. Large modern retail stores, on the other hand, offer a much wider selection, with 15,000 to 20,000 items available to customers.

There has also been a noticeable surge in average order value among quick commerce players, which has risen to up to 650 rupees ($7.8) from the previous range of 350 to 400 rupees. This increase in average order value sets quick commerce apart from kirana stores, where customers typically spend between Rs 100 and Rs 200 per transaction.

While the convenience offered by quick commerce is undeniable, profitability remains a concern for investors. Blinkit — which Zomato acquired in 2022 — aims to achieve adjusted EBITDA break-even by the first quarter of fiscal year 2025, while Zepto has set its sights on EBITDA profitability in 2024. Swiggy’s Instamart is also focusing on profitability, with the parent company indicating that the peak of investments in the business is now behind them. Swiggy turned its food delivery business profitable last year.

Many of these players are trying to improve their margins by increasingly looking beyond the grocery category. All the top three players today sell consumer electronics items, a category that makes about half of the sales on Flipkart and Amazon India by GMV, according to people familiar with the matter. (So it should not come as a surprise that Flipkart is weighing entering the quick commerce market by as early as May this year.)

Additionally, advertising revenues currently account for around 3% to 3.5% of quick commerce platforms’ total revenue and could easily reach 4.5%, primarily driven by direct-to-consumer platforms, BofA said. These platforms are also exploring private label strategies in certain categories, it added.